Madvillain (MF Doom and Madlib) team up with director Daniel Garcia to paint a bleak and foggy video where the robotic banality of modern life is fought with the individuality of the hero…

VIDEO: "Monkey Suite" directed by Daniel Garcia

The reason Batman is a better superhero than Superman (stay with me here) is because the former creates himself from the inside out, whereas the latter is given his super abilities from birth. Batman is something we can aspire to be, Superman is above and beyond our grasp forever.

Madvillain is an anti-hero character that captures much of the same aesthetic and emotional power as Batman. In the video for “Monkey Suite” we immediately plunge into the modern industrial world through the top of a giant smoke stack. The smoke from this factory bleeds into every corner of this world and the screen itself. The weight of a world run on technological blandness moves beyond simply the workplace, but its' smoke creeps around the barstools and roads leading home as well. Madvillain walks against the grain as his fellow beings move dejectedly through the fog in the other direction. ‘Villain speaks about never resting behind a “computer desk” and in his words he hopes to inspire his listeners away from simply conforming to the norm. The same can be said for the video as well, but like Batman - it isn’t your typical call for individuality.

More than simply celebrating the unique qualities and potential for greatness that we all have, sometimes society requires heroes and leaders to show everyone their collective potential before they can do anything with it. Thus Madvillain puts on his uniform and walks through the streets intentionally disguised, the mystery behind the mask is what inspires people to believe in something more than the doldrums of their day-to-day lives. Essentially disguising one’s own place in this assembly line reveals everyone’s ability to escape the same submission.

The mask becomes a symbol of individuality, even in hiding the “truth” of appearance. And in redefining his “truth,” Madvillain becomes a beacon for the rest of his community. This concept is mirrored in the name of the character itself, a reinvention of normally negative ideas as positive ones - thus removing people from their guilt and consequent self-doubt. Madvillain's light shines through and breaks the smog that hovers over everything. He turns heads and raises spirits simply by walking down the street in a different way. It’s a simple video with a fairly simple message, but it is in fact presenting an idea that is rare in popular culture.

The creation of myth and the power of symbols are often less heralded than the ability to directly tell truths, or be “real.” But Madvillain and their director recognize the danger of becoming one of the crowd, and that it's possible raise spirits and inspire people towards greatness by using and celebrating image – rather than rejecting it as false masquerading. There is often more truth in disguise, especially when it creates heroes like Madvillain and Batman.

Tuesday, October 31, 2006

Monday, October 30, 2006

It Don't Feel Right

The Roots combine three songs from their latest album, Game Theory, into one video that produces mixed results. But there are shadows of a theme that linger and persist through all three…

VIDEO: "It's In the Music/Here I Come/Don't Feel Right Medley" The Roots

Game Theory is a great album because it harkens back to the best of The Roots past while still revealing new insights and fresh concepts. In making this video they’ve chosen three songs from that album that highlight its strengths, revealing an emphasis on beats that are both soulful and perfectly matched to Blackthought's smooth cadence. Yet the songs are not simply on display to sell that record, they have a common thread that this video brings out cleverly and clearly, and one that at times works brilliantly.

Blackthought begins on the streets, forming out of a shadow. The imagery sets the mood, gritty and alive – an environment in which ‘Thought excels lyrically. The figures on the brick walls exchange in a number of activities from drug deals to fist fights. Then many of these figures are beaten down by the police, who will eventually begin chasing ‘Thought himself. In combination with the song, which implores the youth and the disenfranchised to find solace in the music, the images on the walls are meant to define the struggle. Words appear on the walls as graffiti art, harkening back to the roots (excuse the pun) of the anti-establishment vibe within the hip-hop movement. More importantly, the word “nomad” signifies what ‘Thought sees as the consequences of this cycle of violence. It not only creates animosity towards the police and government, but also towards the youth within the minority communities, and thus it separates and divides; eventually leaving everyone feeling even more alone.

So it isn’t a coincidence that when the next track starts our rapper is running from the police, on his own. He’s moving through the neighborhoods of his hometown, Philadelphia, and as they expand and contract he cannot seem escape the shadows of his youth, the shadows of that mistreatment and inequality. Faced with such an imbalanced system at such an early age, many kids are forced into the crime game to feel any sort of belonging, let alone support for their families and selves. Now moving into adulthood they are still haunted by the memories of those crimes and both the guilt and anger associated with them. The system has trapped them from the earliest age within the confines of poverty and criminality.

In the final sequence this comes vividly to life with “Don’t Feel Right,” where ‘Thought is brought in to be questioned by the “authorities.” There is not only factual evidence of a discrepancy, but in the use of the lie detector there is the implication that these facts are hidden or disguised intentionally. In a trick that was also recently used in the Taking Back Sunday video for “Liar,” the detector’s results come alive to depict the actual truths of life in America. Many of these images we’ve seen in the shadows of the first part of the video, and here they re-emerge in the interrogation room of a convicted criminal. The point is, there is an entire history behind certain crimes, and if the problem at the core isn’t solved, than the situation will never resolve itself. The Roots and their director want to place the blame, based on the final image, in the police brutality and inequality of the impoverished neighborhoods where the cycle of violence is born.

But on an even deeper level, this problem runs to the heart of the way in which we want to govern our society. We choose to use punishment as a method of deterring violence, but punishment is violence. And whether it is a random beating or even a verbal assault, the debasement of a human being will never inspire that person to change towards something great. This type of punishment destroys morale, erases self-confidence and makes us all “nomads” left to fend for ourselves in a world seemingly out to get us. The pain, shame and self-hate that are intentionally induced by our system of punishment are what make lifetime criminals. If you convince someone they are “bad,” it becomes ten times harder to ever show them that they can be “good.” Jails simply hide criminals, they don’t fix anything.

VIDEO: "It's In the Music/Here I Come/Don't Feel Right Medley" The Roots

Game Theory is a great album because it harkens back to the best of The Roots past while still revealing new insights and fresh concepts. In making this video they’ve chosen three songs from that album that highlight its strengths, revealing an emphasis on beats that are both soulful and perfectly matched to Blackthought's smooth cadence. Yet the songs are not simply on display to sell that record, they have a common thread that this video brings out cleverly and clearly, and one that at times works brilliantly.

Blackthought begins on the streets, forming out of a shadow. The imagery sets the mood, gritty and alive – an environment in which ‘Thought excels lyrically. The figures on the brick walls exchange in a number of activities from drug deals to fist fights. Then many of these figures are beaten down by the police, who will eventually begin chasing ‘Thought himself. In combination with the song, which implores the youth and the disenfranchised to find solace in the music, the images on the walls are meant to define the struggle. Words appear on the walls as graffiti art, harkening back to the roots (excuse the pun) of the anti-establishment vibe within the hip-hop movement. More importantly, the word “nomad” signifies what ‘Thought sees as the consequences of this cycle of violence. It not only creates animosity towards the police and government, but also towards the youth within the minority communities, and thus it separates and divides; eventually leaving everyone feeling even more alone.

So it isn’t a coincidence that when the next track starts our rapper is running from the police, on his own. He’s moving through the neighborhoods of his hometown, Philadelphia, and as they expand and contract he cannot seem escape the shadows of his youth, the shadows of that mistreatment and inequality. Faced with such an imbalanced system at such an early age, many kids are forced into the crime game to feel any sort of belonging, let alone support for their families and selves. Now moving into adulthood they are still haunted by the memories of those crimes and both the guilt and anger associated with them. The system has trapped them from the earliest age within the confines of poverty and criminality.

In the final sequence this comes vividly to life with “Don’t Feel Right,” where ‘Thought is brought in to be questioned by the “authorities.” There is not only factual evidence of a discrepancy, but in the use of the lie detector there is the implication that these facts are hidden or disguised intentionally. In a trick that was also recently used in the Taking Back Sunday video for “Liar,” the detector’s results come alive to depict the actual truths of life in America. Many of these images we’ve seen in the shadows of the first part of the video, and here they re-emerge in the interrogation room of a convicted criminal. The point is, there is an entire history behind certain crimes, and if the problem at the core isn’t solved, than the situation will never resolve itself. The Roots and their director want to place the blame, based on the final image, in the police brutality and inequality of the impoverished neighborhoods where the cycle of violence is born.

But on an even deeper level, this problem runs to the heart of the way in which we want to govern our society. We choose to use punishment as a method of deterring violence, but punishment is violence. And whether it is a random beating or even a verbal assault, the debasement of a human being will never inspire that person to change towards something great. This type of punishment destroys morale, erases self-confidence and makes us all “nomads” left to fend for ourselves in a world seemingly out to get us. The pain, shame and self-hate that are intentionally induced by our system of punishment are what make lifetime criminals. If you convince someone they are “bad,” it becomes ten times harder to ever show them that they can be “good.” Jails simply hide criminals, they don’t fix anything.

Saturday, October 28, 2006

Week in Review

Highlights from the past week on Obtusity...

The Streets give a nod to The Shining, Thom Yorke laments the drowning voice of the individual, and MySpace becomes art in the hands of Bow Wow and Chris Brown.

Check back Monday for new posts, thanks.

Friday, October 27, 2006

Opening Doors to the Self

Science of Sleep director Michel Gondry applies his signature home made special effects to the wacky world of Beck’s “Cellphone’s Dead” in this trippy video that falls somewhere between existentialism and the singer’s own brand of Scientology.

“Going through the motions/Just to savor they did it/Treadmill's running/Underneath their feet…”

When we imagine being lost in the desert with a “dead” cell phone, we immediately think of the horror of being completely disconnected from society. In the age of the Internet it’s paramount to not just have a cell phone, but to stay linked at all times in every way possible. We don’t just have answering machines; we have e-mail, Facebook and instant messaging to make sure we never miss a chance to interact with each other. But even as the world seemingly shrinks daily, actual human connections don’t seem to be increasing all that rapidly. In fact, what Gondry and Beck hone in on is this ironic feeling of isolation in an increasingly “connected” world.

The often ramshackle-nature of Beck’s lyrics may imply nonsense, but they are not intended to be so (except to perhaps underline the alienation of the theme). He sings, “God is Alone,” but we soon see that so is everyone else. The video begins with a tilted shot of a cardboard world in traffic jams, then moves around to focus on the entering Beck, dressed in his worst car salesman get-up yet. What we notice right away is that the viewpoint of the camera is not with Beck, the typical protagonist. It’s viewing him from somewhere else, perhaps somewhere in his own mind, but distinctly separate from the physical Beck as well as the two “creatures” that enter the room.

The camera spins gloriously around the dimly lit apartment without ever making a distinct cut, instead relying on camera tricks and animation to smoothly transition from one scene to the next. Gondry has now mastered these techniques that he previously implemented in a number of videos, as well as in his major pictures such as Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind and the aforementioned The Science of Sleep. The low-fi aesthetic of the camera work gives the video a strange feeling of simplicity and “naturalism,” when in fact its’ themes revolve around feelings of disenchantment with modern technology-obsessed times.

Beck enters the room paranoid, as if being followed, but he also seems to be looking for something. He turns the music up but the “radio’s cold,” and soon enough strange things start to jump through the window. There are two other main characters in the video, one is a building (perhaps a representation of the corporate, or “federal dime”) and the other is a wooden door, both inanimate objects come to 3-D life. The three characters begin to merge and fold into one another, matching the fluidity of the moving camera with a series of closing and opening of doors, windows and dressers. The implication here is that these three are one in the same, representing the different natures of one human lost in a city filled with “hybrid people” – trying to find himself.

There is a futile sense to the video as it endlessly loops around until finally the three beings crash into each other and we are left with the car salesman on his couch wailing, “eye of the sun.” There’s a hole in Beck’s heart, and it emerges from a distinct feeling of isolation from humanity – but there are no phones ringing to reconnect him. There is only the sun, which perhaps is a call to rediscover our natural roots, or maybe it’s a reference to Beck’s own faith in Scientology. Regardless, it’s clear that with the video Gondry is picking up on this simplistic urge, and underlining the difficulty of finding a soul amidst the “juggernaut” of modern times.

Moreover, the sad final image of the dwindling singer in his chair staring at a sun out of it’s “socket” implies graver consequences for our obsession with communication than the death of cell phones - and I’d like to think it has more to do with Al Gore than L. Ron Hubbard.

VIDEO: "Cellphone's Dead" Beck

“Going through the motions/Just to savor they did it/Treadmill's running/Underneath their feet…”

When we imagine being lost in the desert with a “dead” cell phone, we immediately think of the horror of being completely disconnected from society. In the age of the Internet it’s paramount to not just have a cell phone, but to stay linked at all times in every way possible. We don’t just have answering machines; we have e-mail, Facebook and instant messaging to make sure we never miss a chance to interact with each other. But even as the world seemingly shrinks daily, actual human connections don’t seem to be increasing all that rapidly. In fact, what Gondry and Beck hone in on is this ironic feeling of isolation in an increasingly “connected” world.

The often ramshackle-nature of Beck’s lyrics may imply nonsense, but they are not intended to be so (except to perhaps underline the alienation of the theme). He sings, “God is Alone,” but we soon see that so is everyone else. The video begins with a tilted shot of a cardboard world in traffic jams, then moves around to focus on the entering Beck, dressed in his worst car salesman get-up yet. What we notice right away is that the viewpoint of the camera is not with Beck, the typical protagonist. It’s viewing him from somewhere else, perhaps somewhere in his own mind, but distinctly separate from the physical Beck as well as the two “creatures” that enter the room.

The camera spins gloriously around the dimly lit apartment without ever making a distinct cut, instead relying on camera tricks and animation to smoothly transition from one scene to the next. Gondry has now mastered these techniques that he previously implemented in a number of videos, as well as in his major pictures such as Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind and the aforementioned The Science of Sleep. The low-fi aesthetic of the camera work gives the video a strange feeling of simplicity and “naturalism,” when in fact its’ themes revolve around feelings of disenchantment with modern technology-obsessed times.

Beck enters the room paranoid, as if being followed, but he also seems to be looking for something. He turns the music up but the “radio’s cold,” and soon enough strange things start to jump through the window. There are two other main characters in the video, one is a building (perhaps a representation of the corporate, or “federal dime”) and the other is a wooden door, both inanimate objects come to 3-D life. The three characters begin to merge and fold into one another, matching the fluidity of the moving camera with a series of closing and opening of doors, windows and dressers. The implication here is that these three are one in the same, representing the different natures of one human lost in a city filled with “hybrid people” – trying to find himself.

There is a futile sense to the video as it endlessly loops around until finally the three beings crash into each other and we are left with the car salesman on his couch wailing, “eye of the sun.” There’s a hole in Beck’s heart, and it emerges from a distinct feeling of isolation from humanity – but there are no phones ringing to reconnect him. There is only the sun, which perhaps is a call to rediscover our natural roots, or maybe it’s a reference to Beck’s own faith in Scientology. Regardless, it’s clear that with the video Gondry is picking up on this simplistic urge, and underlining the difficulty of finding a soul amidst the “juggernaut” of modern times.

Moreover, the sad final image of the dwindling singer in his chair staring at a sun out of it’s “socket” implies graver consequences for our obsession with communication than the death of cell phones - and I’d like to think it has more to do with Al Gore than L. Ron Hubbard.

VIDEO: "Cellphone's Dead" Beck

Thursday, October 26, 2006

MySpace As Art

VIDEO: "Shortie Like Mine" Bow Wow feat. Chris Brown

The insane popularity of MySpace, especially over similar peer-to-peer competitors, is largely rooted in the easily customizable format of the MySpace “profile.” Users can add everything from hand-drawn backdrops to music videos from their favorite artists. While much of the motivation for making such profiles comes from a desire to connect with others, add new friends (sometimes just famous friends) and often to promote one’s own career, it’s also essentially about expressing one’s individuality simply for the sake of expressing it.

This video explores the concept of individuality by focusing on the unique nature of a number of different girls from around the world. While Bow Wow and Chris Brown each proclaim there is no girl out there like “mine”, we meet a number of beautiful girls, many times simply through an actual profile picture. And though we simply get surface descriptions of each girl, it mirrors the way in which MySpace does provide some insight into a person’s actual life despite remaining an inanimate web page.

Bow Wow, Brown and even Jermaine Dupri all reveal an individualized “page” that is meant to represent them in someway. These pages come to life, and the singers are literally almost brought into the homes of the girls. At some level this simply about promotion, a clever visual trick to get all their fans to run to the computers and obsess over the music and the celebrity status of the performers. But unlike almost every other video these days that is about promotion, the artists here actually find a way to relate to their fan base rather than alienate them with images of extreme wealth and sexuality (on a side note, Chris Brown always looks like he’s having so much fun when he dances). And in the particular emphasis on promoting their “profiles” they do capture the strange phenomenon of adding musicians and celebrities as “friends,” as if the label somehow proves the truth of the relationship. But in fact the addition of celebrity friends is just another aspect of the profile, another expression of individual taste and thought.

The video also delves into the idea of online dating, and the ways in which it can be both successful and frustrating. On the one hand the excitement of “messaging” and online flirting is exemplified in these exchanges, but at the same time we realize that Bow Wow is simply playing games with most of these girls. In the end he chooses the one that he can see in person and directly pursue – looking at each other’s profiles all day isn’t always enough for a relationship. But it would seem that most people are already aware of that.

We don’t use light green font or a hot pink border to just get a date or receive some message from a superstar, we do it simply to express. The visuals of the video, which is a MySpace profile come to life with it’s scrolling text and floating heart-shaped icons, underlines the truly artistic nature of “profile” creating. It’s not just about choosing the right backdrop or having a lot of friends, but everything from the quotes in the “about me” section to the formatting of the “comments” box is about self-expression. And whether we are aware of it or not, there is something truly cathartic in putting together a representation of oneself. Though it also promotes spending hours upon hours on perfecting one’s own image, the creating of “profiles” allows for an artistic outlet that anyone can participate in and everyone can enjoy. Some may argue whether or not its really “art,” but that’s beside the point, what really matters is that people are expressing themselves to each other all over the world – and that’s a good thing.

Wednesday, October 25, 2006

There Are Too Many Of Us

VIDEO OF THE WEEK

VIDEO: "Harrowdown Hill" by Thom Yorke

Much has been made about how the Internet has altered our conception of “truth,” at least in terms of newsworthy events. Twenty years ago if you wanted the facts about a war in the Middle East, all you had was the nightly news and whichever print publications chose to cover the event. Nowadays you have thousands of websites and blogs, multiple 24-hour news stations and the continued presence of print journalism searching for that same “truth.”

On some level Thom Yorke’s video for “Harrowdown Hill” is in support of this Internet phenomenon. The bird’s eye-view that most major news services attempt to give, meaning the general impression of an event, is almost always far too narrow and biased. Yorke and his director celebrate the individual voice amongst the crowd; every hand, every incident that helps create that view. It’s important to realize that in every creative product, every political movement - every moment - there are multiple stories and multiple angles.

Thus we get the blurred images from above the land, which at first almost seems like a miniature model world. But on closer inspection these landscapes are real, just seen through the lens of a generalized vision. The fear here is not that we miss the forest for the trees, but that we miss the dead body on a roof while admiring the vastness of a cityscape.

But while that man lays alone on a rooftop, protestors march through the streets below. There is something to be said for mass movement, and the power of banding together for a cause. The images of struggle are perhaps the most affecting in the video, with large groups of the oppressed fighting the “system.” But even in these cases you can’t help but focus on the particulars of the images; for instance the trampled body under the hooves of armed police.

There will always be a choice in what we hear, read, and see. It is perhaps impossible to ever truly both see the big picture and focus on the particular, but our vision of the general does directly influence the way in which we see the individual. I’m assuming when I see video of protesters, that the police are in the wrong, and thus the trampling of a body takes on certain significance for me. So if we take a closer look at that bird in the sky it looks a lot like a certain species of bird. Whether or not it is meant to be an eagle, and thus perhaps represent the United States, it is clear that Yorke and the director are commenting on the current war with the deluge of images of resisting authority. It is amongst this sea of violence that the individual voice and individual pain are lost, as Yorke struggles beneath the water to find some truth. The artist or anyone attempting to express uniqueness drowns amidst the colossal effects of war, and the collective nationalistic ideology behind it.

Yorke laments, “I can’t take the pressure/ no one cares if you live or die,” and it’s a sentiment that seems to become especially true in times of war. But the final images of the vastness of our world also draw that conclusion out of its limited context. Because in a sense, amidst the sea of humanity and the sea of natural beauty, won’t the individual voice always drown? It’s thus the responsibility of the artist to resist that, and the responsibility of all people to search for those unique, individual perspectives on life.

The “truth” remains elusive, but the more voices we hear the closer we get.

(this esssay was also posted on Blogcritics.org, a site that Obtusity recently joined consisting of a collection of the best bloggers on the internet)

VIDEO: "Harrowdown Hill" by Thom Yorke

Much has been made about how the Internet has altered our conception of “truth,” at least in terms of newsworthy events. Twenty years ago if you wanted the facts about a war in the Middle East, all you had was the nightly news and whichever print publications chose to cover the event. Nowadays you have thousands of websites and blogs, multiple 24-hour news stations and the continued presence of print journalism searching for that same “truth.”

On some level Thom Yorke’s video for “Harrowdown Hill” is in support of this Internet phenomenon. The bird’s eye-view that most major news services attempt to give, meaning the general impression of an event, is almost always far too narrow and biased. Yorke and his director celebrate the individual voice amongst the crowd; every hand, every incident that helps create that view. It’s important to realize that in every creative product, every political movement - every moment - there are multiple stories and multiple angles.

Thus we get the blurred images from above the land, which at first almost seems like a miniature model world. But on closer inspection these landscapes are real, just seen through the lens of a generalized vision. The fear here is not that we miss the forest for the trees, but that we miss the dead body on a roof while admiring the vastness of a cityscape.

But while that man lays alone on a rooftop, protestors march through the streets below. There is something to be said for mass movement, and the power of banding together for a cause. The images of struggle are perhaps the most affecting in the video, with large groups of the oppressed fighting the “system.” But even in these cases you can’t help but focus on the particulars of the images; for instance the trampled body under the hooves of armed police.

There will always be a choice in what we hear, read, and see. It is perhaps impossible to ever truly both see the big picture and focus on the particular, but our vision of the general does directly influence the way in which we see the individual. I’m assuming when I see video of protesters, that the police are in the wrong, and thus the trampling of a body takes on certain significance for me. So if we take a closer look at that bird in the sky it looks a lot like a certain species of bird. Whether or not it is meant to be an eagle, and thus perhaps represent the United States, it is clear that Yorke and the director are commenting on the current war with the deluge of images of resisting authority. It is amongst this sea of violence that the individual voice and individual pain are lost, as Yorke struggles beneath the water to find some truth. The artist or anyone attempting to express uniqueness drowns amidst the colossal effects of war, and the collective nationalistic ideology behind it.

Yorke laments, “I can’t take the pressure/ no one cares if you live or die,” and it’s a sentiment that seems to become especially true in times of war. But the final images of the vastness of our world also draw that conclusion out of its limited context. Because in a sense, amidst the sea of humanity and the sea of natural beauty, won’t the individual voice always drown? It’s thus the responsibility of the artist to resist that, and the responsibility of all people to search for those unique, individual perspectives on life.

The “truth” remains elusive, but the more voices we hear the closer we get.

(this esssay was also posted on Blogcritics.org, a site that Obtusity recently joined consisting of a collection of the best bloggers on the internet)

Tuesday, October 24, 2006

Still So Young

VIDEO: "When You Were Young" The Killers

The opening and closing shot of this video feature a prominent white crucifix, the ultimate historical symbol of purity and innocence. Complimenting this idea is a beautiful young woman in all white, a direct reference to the concept of the "virgin." But she's crying, and suddenly there are flashes of a darker past - and in fact the male protagonist truly "doesn't look a thing like jesus."

The loss of innocence is not a new subject for the Killers. In fact the triumphant single "Mr. Brightside" was partially dealing with the same concept of self-illusion vs. reality. But the religious iconography of both the song and now the video point to a different sort of "loss" in "When We Were Young."

After the foreshadowing of the opening we are plunged into the middle of the story, the woman praying at the church. She emerges to find her lover standing with a cross behind him, exactly in the middle - he seems ideal in her mind. But we quickly learn that he is anything but, and she catches him cheating in her own bed. As she flashes through the idyllic images of the beginnings of love we might anticipate that this is a classic tale of the innocent virgin corrupted by the dirty older man.

But then there is that highly sexualized scene with the water washing across the woman's bare feet and thighs as the man literally licks his lips in lust. In this image there is the hint that perhaps she was not as "innocent" as we had thought. The lyrics of the song seem to point us in that direction as well, "waiting on some beautiful boy to save you from your old ways." She arrives in his bar looking for "work," whatever type of work it is - she clearly sees that he keeps women around and then gets rid of them quite easily. That doesn't bother her, because what she is seeking is re-birth at all costs.

Both of the characters see in each other the chance to start over. The man sees in her the "perfect" virgin and the chance at being a "man", and the woman sees in him "jesus" the savior and the chance at fulfilling her "womanly" role. And while the woman is perhaps more idealistic than him, her complete belief in the ideal is what prevents her from seeing the truth of the situation. It's this same complete belief in ideals and symbols of perfection that let her come back to him after he cheats, and it’s also what leads him back to her. There is no loss of "innocence" in this story, just the cycle of pain that comes from striving to hold to an image of perfection.

They both end up back at the cross, kneeling, crying. There is no hope in this image, simply the foreboding idea that the cycle continues. Every step, from the whiteness of the marriage day to the blue sky above the cross, is marked with an extreme belief in the need and ability for purification. But what neither character understands is that "purity" is not a real thing, it's a harmful concept dreamt up by society to keep people in line; to instill fear in our hearts so that we might not fully experience the joys of life. The religious ideas of virginity, of the savior and everything that they imply are all dangerous to our self-image and our confidence in not only ourselves, but humanity as well. That is the sadness that rests on the final image of the two embracing lovers; it's not that their hearts are broken, but the fact that they pursue a dream that they will never achieve and one that is in fact the root of all their pain.

Monday, October 23, 2006

The Horror In the Bedroom

VIDEO: "Prangin' Out" by The Streets

Mike Skinner has ventured into the world of drugs a number of times on record (and presumably elsewhere as well), but with the video for “Prangin’ Out” director Dawn Shadforth captures the fear and paranoia of drug abuse and expands it to a more universal level, finding themes in The Streets work that aren’t always as blatantly visible.

The cinematography is fluid and effective, creating a feeling of presence and mood that alludes specifically to The Shining but also recalls the feel of more recent horror films such as The Ring. The creepy camera panning across vacant and blandly colored spaces increases the building tension of not only the entire video, but each individual shot also captures the aura of imminent danger. The storytelling is also particularly effective in keeping the viewer compelled, while also sending shivers. The girl that Mike brings home is visually merged with another girl, one who looks distinctly freaky. A mysterious force blows pieces of paper away from Skinner, and in general the tale is told out of order, moving backwards and forwards in time fluidly. There are numerous shadowy figures emerging from darkness and quickly edited shots between seemingly dead and living people. The collection of these images gives one an immediate sense of confusion and discomfort, but on repeated viewings the plot becomes much clearer.

Yet regardless of whether or not one chooses to decipher the exact sequence of events, what becomes obvious is that this tale of drug-induced paranoia is in fact more about the self-doubt that plagues all of us. The potentially murderous past and future of the character Skinner plays in the video is a play upon his own regrets and “failures.” He often discusses past relationships and their eventual destruction in his work, and it’s this constant reminder of failure that prevents him from embracing a new love. It comes vividly to the screen in the bedroom scene where Skinner is unable to embrace the girl beside him because he's constantly reminded of his hideous past. He lets his demons control him and for that reason he not only fears new intimacy, but he also causes others to fear him (i.e the girl has visions of dead people as well). It’s this defensive mechanism that takes over in his mind at moments of weakness, and though he isn’t lashing out through acts of insanity or murder in the real world, he is turning to cocaine for relief.

The Shining allusions shed further light on the correlation between the song and the video. What Skinner slowly realizes is that he has suppressed something in his mind that is perhaps horrendous, but its something that will not stay dormant forever. We feel this fear of our inner “beast,” the savage ferocity of our passions that could at any moment take over. Todd Field’s In the Bedroom was a powerful study of the way in which society pushes these thoughts into the farthest corners (the privacy and isolation of the bedroom) until they have no choice but to emerge, and “Prangin’ Out” is working amongst the same themes. The hotel that Skinner roams is filled with strange characters and dirty secrets, and as he begins to explore the corridors of his mind he finds that there are dark places that he may not even be aware of.

But while this fear of finding something terrible may often prevent us from exploring our own thoughts, Skinner is an artist and one who specializes in bringing his inner most worlds to life. And thus it is through the act of writing (the paper that eludes his grasp leads him to the chilling bathroom scene) that he begins to catch glimpses of his fears, his guilt and where they originate. Unfortunately the paranoia and madness win in this particular instance, and it serves as a harrowing reminder of the need to deal and overcome our guilt, no matter how difficult and scary that may seem.

Sunday, October 22, 2006

Real Shit?

VIDEO: "On Some Real Shit" Daz feat. Rick Ross

The most vital strand of hip-hop ideology is founded in the need to express unity and uniqueness in the same breath. While on one hand the corners that held revolutionary rappers, break-dancers and graffiti artists where reacting against the prevailing racially and socially discriminative society, they where also bringing together the neighborhood; the “block.” There was an urge to not only separate from and defeat the oppressive powers, but to also keep families and culture alive. In today’s hip-hop scene there is less of a distinct fight against the inequities of society (though that’s not to say they’ve disappeared), instead what remains is the obsession with differentiating one’s “hood” in hopes of elevating one’s own unique talent. What may be lost in the shuffle though, is the urge to unify.

The idea of “hood pride” can be extrapolated to represent entire sections of America, and artists intentionally ascribe to different styles and movements in order to explain where they are from. The video for “On Some Real Shit“ is like many modern hip-hop videos in that it is attempting to define a particular locality through types of music and types of images.

Former Deathrow MC Daz arrives in Miami, greeted by the newest “king of Miami” Rick Ross, by saying “it’s just like California.” Presumably the rest of the video is an attempt to repute that claim by showing the unique quality of Rick Ross’ Miami. Everything from the purple cars decorated with vibrant designs (a continuation of graffiti art) to the particular locales at which these rappers party is meant to define Miami as different, and perhaps more fun than wherever you come from.

And yet while this aspect of the video captures some of the cultural importance of hip-hop, in that it gives voice to disenfranchised groups from places all over the country, it also falls prey to an all too common practice. Miami is defined not only by its car designs, tropical destinations and blue skies – but its particular “types” of women as well. And perhaps the idea of beauty centering on locality is an automatic function of comparative discussion on the topic (probably not), but it definitely doesn’t need to be as objectifying as it is here.

The word “objectification” is thrown out a lot in relation to hip-hop videos, so much so that in many circles it may have lost its value as valid criticism. Regardless, it’s clear that it isn’t taken very seriously. The problem here is not just that the image of scantily clad women dancing about and succumbing to “powerful” rich men reinforces stereotypes and standards of sexual relations that have plagued society for centuries, but more importantly it’s the fact that these women are blatantly associated with objects. They dance in front and around those very cars that define Miami, they are of certain ethnic descent – meant to depict the variety of women in the area and they are dressed in colors meant to further that differentiation. But its that image of girls and cars that stinks the most, as the woman in front of the black car is dressed in all black and the one in front of the purple car is dressed more colorfully; these women are literally just extensions of the objects themselves.

This is a song about one group of men showing off their individuality and skill to another group of men. Everything from the fresh fun sound of the beat to the riding cinematography of the opening sequence is meant to both recall and then improve upon the traditional coastal rap image, i.e. that of the west coast. The women in the video are just an expansion of this bravado, further "proof" that Miami is better than L.A. It’s not just that they are sexual objects, meant simply to please men, but they are also just plain objects, like a baseball trophy you show to your friends to signify “manhood.”

It’s a significantly dehumanizing concept, and more than the words in the song, the blatant imagery of this video brings this increasingly popular idea to the forefront. It’s neither unique nor unifying. In fact, the individual voice is almost lost amongst the rubble of misogyny in hip-hop – it’s hard to focus on the uniqueness of the music when the imagery is all the same (Lloyd Banks "Hands Up" is another recent example of the same theme). And it’s definitely not unifying when an entire sex is regarded merely as graffiti art on the side of a cool car.

Thursday, October 19, 2006

Week In Review

Highlights from the first weeks of Obtusity...

Sex and love symphonize in Justin Timberlake's new video, the Guillemots deliver one of the best albums of the year, and two birds fight the age old battle of the human conscious in "The Owl."

Regular posting will resume Monday. Peace.

Escaping The Owl

VIDEO: "The Owl" I Love You But I've Chosen Darkness

Somewhere in every human heart there is the owl.

This deep motivating fear keeps us both reaching for the light and struggling to be free. Yet the bird that holds us back is not just a product of our mind, it is hatched elsewhere.

This brilliant video from I Love You But I’ve Chosen Darkness (either the best band name ever, or the most pretentious) subtly develops a complex world of jailed emotions and a growing terror from inside. The animation is startling, beautifully detailed and yet so simple in its use of colors and sharp lines. The focus on the crow’s dilated pupils is a masterstroke, emphasizing the emotion from the opening shots while echoing the horror-flick soundtrack-ness of the song. There is a blind instinct of survival in the crow, it closes its eyes only to blink from necessity, otherwise it is firmly fixed on the owl protruding out of the darkness.

But for the first half of the video we are unaware of what it is that causes this intense fear. It opens with a stunning series of images; the string that shakes with the guitar chords, the opening of light and the claw caught in that same string. The story builds on the falling objects that hit and skew past the captive animal. Particular emphasis is given to a stick of lipstick, which falls in slow motion towards the bird. There is also a soda can tab and a fast food box; trash mostly. But more than that these objects represent something of our modern culture, if nothing else this fast food ideology of instant gratification. And perhaps the warbling string is a reference to the role popular music plays in this process. We consume and we move on in order to avoid looking inside; inside where this epic battle between hope and despair rages. But it’s that falling lipstick that is the most chilling reminder of how our obsession with outer appearance is also rooted in a fear of ourselves, and more disturbingly, it’s a self-image that is reinforced by popular culture and our society. We would almost prefer hiding behind masks than having to face our “hearts of darkness.”

The video, of course, finally unveils itself with the shocking revelation of the owl. Stoic and far less visible, there is a truly sinister quality to the bird whose feathers ever so slightly waver in the wind. Owls are not typically the most terrifying of birds, in fact, the crow is traditionally a symbol of death and evil. But owls come out at night, and owls hoot and hide in shadow during the day. It’s an awesomely powerful image. The depth and skill of the animation and direction of this work cannot be overstated. It's breathtaking and almost overwhelming in it's tension; a complete mastery of form.

But what is key to this entire process is realizing that both the owl and the crow are emerging from the same darkness. The crow is tethered by his own fear, his panicked attempt at escape is not succeeding because he is constantly conscious of the owl that “hunts” him. That is not to say that we have nothing to fear, it would be naïve to assume that thousands of years of social mores and customs can be erased from our psyches in one fatal swoop. But we can overcome the terror of being ourselves, this fear of the light. Because in the end, that is what we fear the most; emerging in the light only to find it less satisfying than we hoped. Yet would we rather toil in this miserable state of constant escape than explore the unknown?

Paris Hilton and More Feminism

VIDEO: "Stars Are Blind" Paris Hilton

They banned this video in India for it’s rampant sexuality. This comes as no surprise to anyone who knows anything about Paris Hilton and her previous “videos.”

“Stars Are Blind” is directed by Chris Applebaum, and from the opening shot it’s referencing 1991’s “Wicked Games” by Chris Isaak, a video that raised similar objections when it first aired. The two videos share shots of water rushing and bodies rubbing, not to mention uniquely bad singers.

But they also share a huge emphasis on female anatomy over male anatomy, choosing to highlight Ms. Hilton and model Helena Christensen over their male counterparts. It’s nothing new to point out the rampant misogyny in pop music, particularly in music videos, but there’s a more interesting question lingering here.

In Isaak’s piece Christensen shows a bit more skin than Paris, but neither is ever fully nude, rather they strut and stare in a sexual manner. Can you imagine the equivalent male poses? Chris Isaak barely takes off his shirt here, and while Paris’ counterpart is definitely meant to be eye candy, he doesn’t move around or touch himself provocatively - and the camera almost always lingers on Paris anyway. Michael Jackson grabbed his crouch emphatically for over 20 years on MTV, and while it angered a few, none of his videos are really considered “too sexy,” but rather somewhat disturbing. Can a guy even be sexy?

Some may remember the D’Angelo video, “Untitled (How Does It Feel),” a few years back where the camera grazed over his completely naked body as he sung soulfully. But D’Angelo is not exactly the same as Paris Hilton. He was a great singer who used his body to compliment a particular songs sexual force, and even then he barely moves throughout the video. And the fact that the camera simply pans over his body as he stands there actually gives him a sort of power; you are forced to hear the lyrics - whereas a dancing Paris seems somewhere closer to a stripper. In fact, “Stars are Blind” is a fairly innocent love song with some playful coded references, but it doesn’t have to be about sex, we just expect as much from Paris Hilton. The reality is, there is no male equivalent in music to Paris.

But does this mean women like Paris or Fergie are being forced into portraying themselves in a certain manner in order to attain a level of success? Probably, and honestly no one can blame Paris Hilton for capitalizing on an opportunity. But what is far more disheartening is the fact that in making a video that references the sexuality of Chris Isaak’s “Wicked Games” the director and Hilton did not choose to reverse the angle. Since the days of Laura Mulvey’s “Visual Pleasure and the Narrative Cinema,” published in 1975, we’ve been fully aware of the male gaze in cinema, but it is clear that not much has changed.

The music industry is still run by heterosexual men and their desires. Christina Aguilera and others have recognized this, and even come out against it, and yet they are still forced to sell their own work based on their bodies. A song like “Ain’t No Other Man” would have been prime for spotlighting a male figure, but it becomes yet another female strut-fest. Isaak and so many other males (particularly in hip-hop) have made videos that are primarily about showing off women, but how many women are making videos that show off men, where are the male video “honeys”? And while there is an unbelievable amount of objectification and dehumanization of females in many music videos, female displays of sexuality should not be banned. Instead one just wishes that someone in the music industry, male or female, would have the guts to do the same with men.

We've Been Through This Too Long

VIDEO: "Ring the Alarm" Beyonce

Beyonce’s fire-igniting “Ring the Alarm” begins with its chorus, which is almost entirely devoted to references to “the other woman.” Our singer fears losing everything she has to another woman, but this song is supposed to be about the inequity of her relationship with a man, right? Though Beyonce threatens her ex with an impending explosion of rage, she also admits that “she can’t let” him go – precisely because of the possibility that he will go to another woman. As the video shows, it is truly a song about female insecurity, the way in which society continually makes females more insecure in relationships than men.

The Sharon Stone scene in the interrogation rooms re-iterates this point about restraining and confining woman, as armed men and police officers surround Beyonce. But what she does to retaliate is use her femininity to actual scare these strong men, they attempt to restrain her but her madness increases. Beyonce and the director play upon the historically popular, yet false, correlation of “lunacy” with woman (derived from comparing “luna”-r cycles and the monthly activities of women). It is this that men fear most, what they cannot (or will not try to) understand, what Beyonce calls her “female intuition.” The sharp cuts and harsh motions of the singer are meant to amplify this affect of rage and fear, but they are constantly juxtaposed against looks of insecurity and sadness on the face of Beyonce.

Against the dark red motif of the jail we have the oceanic window where Beyonce sits almost make-up less and vulnerable. As much as she is trying to be mad, as much as she is attempting to raise a fire of vengeance – she can’t help but be afraid that she is losing something that she may not ever get again. It is no great insight to proclaim that men are more confident in their relationships with women than vice versa, mainly as a result of a system that favors aging “experienced” men and young “virginal” women. And it’s the remnants of this outdated (as if it ever had a “date” when it was acceptable) ideology that influences the constant doubting of wronged women. We all can understand the pain of being hurt combined with the fear of loss and starting over, but we can’t at the same time deny that this feeling is heightened among women – especially in popular culture. How many comparable anthems can we find sung by men? Especially in hip-hop?

But the video is aware of this. There is a building confidence in the tone of the work, and by the end our hero is in fact playing a part more than actually going insane. What she realizes is her power lies in her expression of anger. The real “alarm” that is sounding across the radio is one of distressed females, still struggling for equality in a hyper-masculine industry and world, screaming for recognition. The red-lipsticked smile that ends the video is a nod to that sentiment – and perhaps a clue to the way in which women can overcome this societal roadblock. Beyonce has always been about voice, her amazingly powerful crescendo is unparalleled in pop music for it's sheer ability to get you to listen. This is a video that attempts to match that vocal power with images of intense feeling. It is through self-expression, especially through this type of passionate self-expression, that people begin to listen and recognize inequities.

Tuesday, October 17, 2006

Welcome To the Black Parade

VIDEO: "Welcome To the Black Parade" My Chemical Romance

What's lost amidst all the mockery that "goth" recieves in modern culture is the truly inspiring core of the movement. Contrary to some interpretations, this isn’t a group of devil-worshipping sad moppy freaks. With “Welcome to the Black Parade,” My Chemical Romance may have finally written the rousing battle cry that not only illuminates the motivating ideas behind the larger movement, but one that could unite the disparate roots of this group into one triumphant "parade" of defiance. Because that is, essentially, what all the make-up, anarchist paraphernalia and battered clothing are all about; the forgotten, the discriminated, the condemned souls of society are all invited to join this black procession against the norm.

The video is successful on it’s own terms in transcribing the ethos of the song, but like all good music videos, it seems to co-exist with the song at every step. Drawing cues from and referencing everything from Persona to 1920’s German Expressionism, the video is scaled and filmed to the epic proportions of MCR’s ambitious production, and perhaps succeeds where the song musically falls short. The marvelous faux-Oz set piece (particularly reminiscent of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari) is the highlight though, with its snow-globe environment cascading around a dilapidating society. It’s precisely that blackened castle in the background, the soaring reminder of what could be, that forms the central theme of the work – and it’s most beautiful image.

The insane hospital that our protagonist begins in is perhaps a representation of the confining hold of “normality” or socially accepted morals. Notice the way in which the bored nurse registers no emotion towards the struggling patient, and more obviously, the stark whiteness of that environment crumbles under the weight of the “black parade” in this man’s dreams. As the singer triumphantly declares “this world will never take” his heart.

The TV screen on which the man sees his song played out is a reference to the band, who have huge ideas about the power of music to inspire. And yet the TV screen cannot help but also reference the very music video that we are watching (as well as the aforementioned Persona) – it’s the type of self-reference that could be tacky accompanied by a lesser song – but MCR are not attempting to hide the epic notions of their craft.

There are other clues to the scope of this vision. The sign that reads, “Starved to death in a world of plenty” is clear, and in the song itself we can hear it echoed in “though you’re broken and defeated, you’re weary widow marches on.” This image of the weary widow is a powerful symbol of hope, ironically dressed in typical images of “fear.” What the filmmakers and band are pushing here is a revisionist ideology; it’s about reaching out and including all those that feel forgotten. Thus when the patient finally goes “insane” he is in fact roaming about the fields of blackness that represent the idyllic future, a world that now only exists in his mind.

And yet perhaps the final shot of the lonely wanderer gives clues to the limits of this concept. We hear from the singer “I’m not a hero/just a boy, who’s meant to sing this song.” But perhaps there is some need for a heroic figure, or at least someone to outline exactly where this procession is headed. The castle in the distance raises spirits, but in utter defiance of conformity has a feasible alternative been found? On some level it may seem that this is simply a surface revolution; change your clothes, wear some dark eyeliner. But if nothing more these surfaces represent a deeper need for revolution and for change, and for that reason alone – MCR and the rest should keep marching.

Mo(u)rning to Wake You: "The Funeral"

VIDEO: Band of Horses "The Funeral"

The distant somber notes of “The Funeral” are brought forcibly into focus through the bleak imagery of this video. For a song that lyrically remains perplexing, even if thematically it screams obvious, this type of layered video is more than revealing.

Much like the lyrics, the video is on the surface quite blatant in its attempt to set mood. The hazy gloss over the entirety of the work plays like the chorus of the song, “At every occasion I’ll be waiting for the funeral,” and it gives it not only the feeling of aging, but also references the earliest artistic techniques of cinema (perhaps citing the death of silent film). But the images that briefly accompany this lonely barstool on his way to death are what give the piece weight and emotional significance beyond just thoughts on death.

The elderly man (who looks somewhat like the now deceased Walter Matthau), begins the clip presumably driving home from work. His hands are on the wheel firmly and he makes sure to use his signal, following all the rules of the road. He pulls over at a local bar for a drink before he heads home. Yet once he gets a few drinks in him, home begins to drift into the distance. The bland repetitiveness of his life begins to creep ever so slightly into his mind. First there is the young girl at the end of the bar that ignores him and perhaps reminds him of past loves, secondly the friendly dog in his drink (who most likely has passed away) pushes forward thoughts on loss, and finally the blurred images of a thousand nights at the same bar on the same barstool.

The elements of his slipping life begin to intoxicate him, and his only recourse is the drink and the record player. He puts on his favorite track, and drowns himself in the liquor. Music has the power to elevate, but it also has the power to amplify misery. Our protagonist falls further and further into the drink and as he recalls his youth one image particularly strikes him. The image of himself as a pilot; giving orders and soaring through the clouds. It would seem that this man had a climactic moment of life, but it passed so many decades before this moment. And while he tragically meets his death, there is something joyous in his final breathes. The way he lets go of the steering wheel, doesn’t use his signal, the way he reclaims the skies and is reborn as a young pilot flying into the sun.

But the monotony of modern life is what lingers on after the video is done. Perhaps it is the monotony of aging, but perhaps it is only when we are aged that we realize how stuck we are in routine. This is why Band of Horses are thinking of their funerals today, at every occasion, even as 20 somethings. Because life passes too quickly, and sooner or later you will be at the bar on that barstool. But the question remains, what will your memories be, and will you always have more to live for?

Live each day as if it where your last is perhaps too simple, but there’s something to it nonetheless.

Monday, October 16, 2006

A World of Water: "All Fires"

LISTEN: Swan Lake "All Fires"

“But this Theresa, they love, the best…”

Mother Theresa was and is a fascinating public figure. She represents “kindness” and “purity” to so many people around the world, across cultures. Mainly as a result of her well-documented charity and social work in impoverished nations. Whether or not Swan Lake is making a reference to this particular Theresa in “All Fires” is beside the point, what we can’t deny is that in contemporary society the name “Theresa” holds with it the weight of a certain “saintly” woman in blue and white.

“From near his heart, he took a rib…”

The rock star is more closely aligned with “Theresa” than one might think. Since the days of romantic poets it’s been fashionable to be a “tragic” artist. And what that has come to mean is sacrifice; suffer for your art. But it isn’t just self-imposed suffering, because society and the public demand it from the great artist, as well as with all great people. The one’s we respect, “love” the best are the ones that give the most of themselves for others, for us.

What this track approximates is our desire and need for martyrdom, that romantic urge for the epic act of sacrifice. But what we can’t ignore is our own impulse for self-preservation, one that emerges blaringly at moments of intense danger.

“500 pieces means 500 float, 1000 people means 500 don’t…”

Krug narrates the story of a village tragically struck by a flood that scrambles to save life as half the community drowns. The solution becomes a nearby church, which they use for flotation wood. Amidst this chaos the mason’s wife swims to save her daughter, disregarding her own safety. At this point the backing vocals increase, and the track intensifies with the line "500 pieces..." What the singer anticipates in the first verse is that above all else we will sacrifice for love. But paradoxically we are driven by self-preservation, and in moments of complete despair we would choose our own lives, at least 50 percent of the time, over either martyrdom or salvation. And it is precisely love, our love of the both the romantic notion and our love of ourselves, that rules both decisions in this case. The romantic and religious ideals are not sacred enough to resist our urge for survival, and yet we insist that life is suffering. It is our love of the idea of “Theresa,” our obsession with the story of Jesus and all the great “sacrifices” in history, that keeps us dreaming of these people. But at what cost?

“All fires have to burn alive, to live…”

To truly inspire people, and to keep them preserving their lives and each other it seems that one must sacrifice something. In the end the singer decides that he also loves “Theresa” the best, and perhaps is deciding to go the way of the tragic figures before him. But there is also the open possibility of rejecting the ideal, or perhaps using it in a different way. The villagers tear up a church to preserve their lives, because in the end, that is more important. There is no denying that impulse. And yet you somehow want to condemn them for losing the life of 500.

But it remains a sad fact that to burn brightly, one must burn first. It would be ideal if we could escape this cycle of self-pain and self-punishment, but how do we break the cycle when we all celebrate it openly? Is sacrifice the noblest of actions for human beings? It shouldn’t be. Great art, like this song, should exist without the necessity of self-sacrifice. That isn’t to say that tragedy doesn’t produce the highest heights of beauty, but to intentionally choose pain in order to achieve beauty is troublesome – and also a very prevalent idea in our society.

This is a poweful song, no matter what stance Krug and company are taking. What they pinpoint is this impulse for pain in all of us, but even more prominently how it affects music, the artist, and us - the audience. Our love of Cobain only inspires more Cobain's, but how can we not love Cobain?

Sunday, October 15, 2006

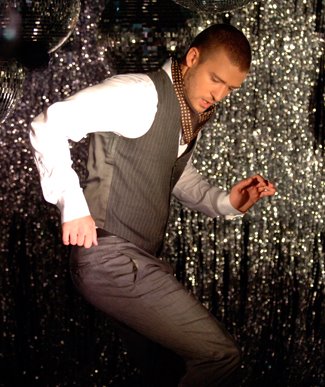

Love, Lust and Icons: "My Love"

Video: Justin Timberlake's "My Love" (Better Quality Video)

The irony of “My Love” is in the frankness of the words, and the hyper-surrealism of the “symphony” of sounds. This is a love song that isn’t actually about love; it’s about the feeling of excitement and lust that anticipates love. Justin Timberlake isn’t writing a love note or a symphony, he’s writing a pop dance song.

But while the song brings up the subject, the video crystallizes the mood and sensual energy of the beat and verses. The “Let Me Talk to You” prelude foreshadows the double meanings of “My Love” with Timbaland’s playful exchange with JT across a mostly black backdrop with streaks of white light. The color choices here are paramount, and by keeping the video in black and white we are more aware than ever of a two-sided game. Much like Gnarls Barkley’s video for “Crazy,” the director is intent on showing us that there is more to “love” than meets the eye.

When the actual song begins we are immersed in a vast white space as JT comes spinning into focus. It’s a slow epic beginning to a song of equal measure, and the slew of cello’s that come flying out of Justin’s vest are a fitting tribute to the theme. This is an upbeat dance number that has a deceivingly slow beat, and the slow-motion effect of objects flying out of the singers captures that dialectic.

The “other side” of love in this case is sex. There is a manic energy to the inter-splicing of the shots (an editing masterpiece), but the way in which highly sexualized images seem to just flash on the screen and then disappear is a perfect way to make a kinky music video. Rather than lingering on any one move, JT and crew do things quickly and smoothly – like the dance moves themselves. Here we have a girl shaking her butt, then we have mysterious gloved hands grabbing Justin’s chest and finally we have the genius use of rubber bands in the scenes with T.I. (“rubberband man”). JT may be trying a bit too hard to sell his newfound sexual freedom, but then again, it’s working.

Above all the video is a clean-cut visual stunner that makes everyone involved look very cool. From the opening shots of the two white suited gentlemen, to the dance scenes that play like the greatest Gap video ever, and finally to that debonair aura of T.I. – this song is about the surface appeal of love. But that’s not to say it isn’t actually “love.” Justin throws a ring at the screen like he means it, and when he sits across from that girl on the couch; I think he does mean it. And even if T.I. plays up the whole misogynistic I don’t care about you role, it doesn’t retract from the one JT is playing. We just have to remember that they are both, just roles.

And perhaps the climactic final shot of JT dancing in tune with a gorgeous girl, and then moving off on his own (all the while the camera spins around him gloriously uncut) is a testament to our love of surface roles. It’s the most cinematic and visually stunning shot of the entire video, and it’s about nothing more than JT. In the end, it doesn’t matter whether or not JT is really in love, because what we really “love” is him – Justin Timberlake, the new king of pop.

Monday, October 02, 2006

Fighting The Shadows

On their debut album, Through the Windowpane, the Guillemots toil in the darkness only to further illuminate the joys of the sun. And in those moments when they soar past Icarus and touch fire - they are a band to behold, reaching heights unheard of in modern pop precisely because of the time spent in the cellars.

Sumptuous strings and subdued melancholic keys punctuate a striking opening for the Guillemots in “Little Bear” where lead singer Fyfe Dangerfield waxes Buckley and declares, “I’m going beneath the stars/I’m going under the soil again/And I won’t be back in a long time.” As he descends into thought the strings grow dark and horrific, the last ten seconds leaving an ominous feeling of anticipation.

But as soon as that feeling settles, a completely new one emerges on track two. “Madeup Lovesong #43” is a deceptively simple ballad, expounding on the simple motivational power of love while breathing through a strange landscape of echoing brit-pop guitars and epic drums. The singer begins in a seeming state of unrequited love, “I love you, I don’t think you care.” But it’s in the final act that Dangerfield lets his guard down, screams like a madman ala Jim James on “Wordless Chorus,” and overcomes his skepticism, “I can’t believe you care!” becomes his triumphant battle cry.

“Trains to Brazil,” like “Made Up Love Song,” has appeared on previous EP’s but it is within this context that it garners its’ true power. Musically it’s the most exciting song of the year this side of “In the Morning” (Junior Boys); combining the jazz impulses of the group with David Byrne yelps and pounding toe-tapping drums - emerging as a thunderbolt of ache, bliss and pure emotion.

Here Dangerfield speaks to his own frustrated impulses, “I wonder why we bother at all,” after he loses a love to “erroneous fools.” Yet further on in the record, on “Blue Would Still Be Blue,” he laments, “I waste so much time thinking about time, I should be out there claiming what’s mine.” Here we are presented with nothing but a stripped keyboard melody to accompany Dangerfield’s high wire vocal acrobatics; we understand the self-doubt at play in the center of this record. The singer himself is in fact one who moans his life “from one day to the next,” but he is also one who celebrates it. It would be naïve to just “live and be thankful,” as Dangerfield himself puts it here. “One day I could die, just like I was born, and the split in the middle is what I’m here for, and I just want to fill it all with joy.”

The album teeters between despair and hope in a painstakingly balanced manner, “shadows on the windowpane” turn into “love coming through my windowpane” from song to song. “We’re Here” wants to imagine the arrival of our trains in brazil on magic carpets and perfect love, but album closer “Sao Paulo” ends crushingly depressed with Dangerfield spiting the world and himself, content to toil in the underground once more – or just leave altogether.

It’s the promise of the world still unseen that continually brings Dangerfield and co. out of this hole, the hope that the light felt in the distance might illuminate something beautiful in their presence or bring some warmth to their bodies. And yet to end on such a somber note is a statement of realism that makes Through the Windowpane so affecting, it offers no solutions but as Dangerfield sings on “We’re Here,” it’s simply an expression of “joy and pain fighting in the corridors.”

www.guillemots.com

www.myspace.com/guillemotsmusic

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Depth of Focus Videographies: Radiohead / Bjork / Michael Jackson / Bowie